First posted on the ORIGINal Thoughts Blog

By Adam Day

CEO, Clear Skies

Medium, bsky, LinkedIn, X: @clearskiesadam

Email: info@clear-skies.co.uk

Take Home Points:

“We write to request withdrawal of our manuscript…” It wasn’t what I expected.

I was a few months into my first editorial job. Not long enough to call myself an expert, but long enough to know the basics. And, basically, there are two outcomes of every peer-review: accept or reject. ‘Accept’ always felt good and the author would sometimes write back to thank us. (That felt good too!) But that day was different. I accepted a manuscript and the author wrote back to request its withdrawal. “Hey, get a loada this guy!” I exclaimed naively.

That was the point at which a more experienced member of staff suggested patiently that I escalate the matter to the Editor-in-chief. Sure enough, it turned out that the paper had been submitted to another journal at the same time. With hindsight, that much was obvious. The authors’ only reason to withdraw after acceptance was because they knew they’d be found out if their paper was published in two places.

That was the first misconduct case I investigated.

My colleagues and I came to see a lot of them—not as many as I see now, but enough to learn that problems of this kind were common. That said, if you had told me that there were companies offering fake research papers for money, I probably wouldn’t have believed you. Having spent some time investigating such companies (AKA “papermills”), I now know that it was certainly happening at that time, just not in places that were visible to me.

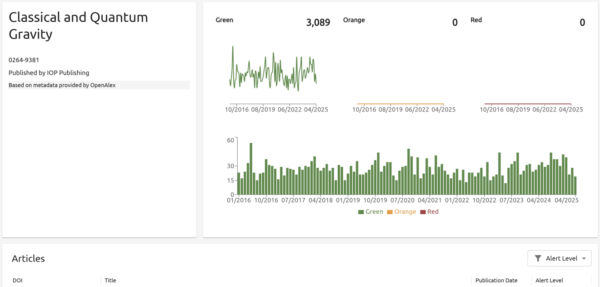

I managed a journal called Classical and Quantum Gravity (CQG) for several years. Around 10,000 manuscripts passed through that journal while I was there. We took misconduct very seriously. If we found it, or thought we did, we would work together—never unilaterally—and follow a procedure to investigate and establish consensus over whether misconduct had taken place. Investigations were slow and hard work. Once we had agreement about how to proceed, then we would respond appropriately. I think that consensus part was important. Even when cases were obvious, it didn’t matter—it was never one person’s decision. I think we did a good job, too. CQG comes up clean on Oversight (an index of journal integrity).

Each bar represents a month’s output for CQG. Green means we didn’t find any signs of research fraud. Full disclosure—I edited the journal until 2015, so I can’t take credit for anything in this image!

It’s nice that we aren’t finding any problems (and I know that we did receive at least one manuscript from the world of organized research frauds), but I would never claim we were running a perfect system. Peer-review simply isn’t perfect. We were reliant on the kindness of others to get things reviewed and we had to put trust in authors not to abuse the system. Most misconduct cases that came up were found manually by ourselves or the referees. In those days, we didn’t have adaptive tools like the multi-award winning Papermill Alarm.

Editorial experience—especially experience of investigating misconduct cases and working directy with all involved parties—has been critical to building Clear Skies’ services to support editorial offices.

We’ve always said that we are not prescriptive about how editors and other integrity specialists use Oversight, or the Papermill Alarm, so there’s no instruction manual. However, I often think about how I would use the tool as an editor and what I’ve learned from the last three years of talking to other editors about their experiences in a changing landscape.

I might write that up in detail at some point, but there are three main considerations:

1. Prepare: what can we do right now, before we see a single case, to put us in good stead to deal with it? How should we manage data and protect the peer-review system?

Screening tools, like those at Clear Skies, will monitor any journal for risk and provide warnings when those risks appear. I’m sure it also pays to give a lot of thought to internal policies and processes including the practical, ethical, and legal aspects. A lot of editors also keep a checklist of things to look for in papers which they consider to be problematic.

From a data perspective, the best advice is to acquire, store, and register good quality data. ORCID is a great opportunity to know your authors well and maintain good data on their scientific activities. If you authenticate all authors with ORCID and ensure the data is recorded in Crossref it makes checking author histories easier for everyone. “Know Your Author” is a good mantra for good integrity and ORCID helps a lot with that.

2. Detect: how do we find them? I know what editorial workloads are like. Time is scarce. What really matters when we need to make a decision fast?

The Papermill Alarm will show you when there are patterns consistent with research fraud. It doesn’t diagnose fraud and so it’s important to have efficient methods to action the alerts. If you see an alert, we recommend always sending papers with alerts to good referees (editors often hold preferred referees in reserve). Oversight can show you what to look for in an investigation. A quick investigation might remove the need to bother referees at all, but I think it’s worthwhile to get their input—their expertise might allow them to see evidence of flaws and that can help you build and maintain that checklist.

But, if you already have a checklist of the things that you consider to be grounds for a decision, you may be able to simply refer to that and move on to the next article. So, again, we can’t be prescriptive, it’s important that editors and publishers can be free to make and change their policies and practices depending on their situation.

3. Respond: and what should we do about it when we do once that decision is made?

The good news is, if you detect a problem before acceptance, you can simply reject the paper. The process is harder when we are dealing with a published article. In that case, we need to find solid evidence supporting retraction.

Disincentives are controversial, but worth considering. When I would find misconduct:

- I would show the author the evidence and get their side of the story.

- If they couldn’t explain it, and there was consensus on our side that misconduct had taken place, we would often issue a sanction, such as a temporary publication ban. I think it was an effective disincentive that protected the business and left the door open for forgiveness. It’s worth saying that COPE guidelines around sanctions have varied over the years and publishers have wide-ranging views on the matter. I hope that my experience here is helpful, but I know that there are some strongly held views about sanctions.

With papermills it’s different. We know that papermills often set up fake accounts in order to submit papers on behalf of an author. If we suspect that we are dealing with a papermill, we should not give them any feedback at all and we definitely shouldn’t tell them how we caught them. As an analogy: treat the submission the same way you would treat a spam email.

If we have good data on authors (e.g., ORCID), that might help us to decide whether an author’s account is genuine, or a sock-puppet account controlled by a bad actor. Our advice would always be to minimise engagement with any account that you believe to be controlled by papermills.

I’ve tried to keep this short. In truth, there’s a lot to say about this. Handling papermills is complex. Partly, it’s about finding what works best for you and we’ve built flexible tools knowing that different editors have different processes. But it’s also about understanding that there are new challenges in peer-review. It pays to know your data, to know your tools and, above all, Know Your Author.

Author’s Note and Conflict of Interest Statement: Adam Day is the CEO and founder of Clear Skies. Clear Skies is an innovator in research integrity screening, having created the first tool dedicated to the detection of organized research fraud: Papermill Alarm. Clear Skies has gone on to win multiple awards, including the 2024 ALPSP Award for Innovation sponsored by PA Editorial. In a former life, Adam was a journal editor—an experience critical to providing integrity services to editors and other integrity professionals.

Editor’s Note: In February of this year, KGL announced a partnership with Clear Skies to integrate Papermill Alarm into KGL’s Smart Review Platform. Read the press release here and KGL’s subsequent interview with Adam Day on research integrity here. For more information about Smart Review, contact Alex Kahler, Director, KGL Editorial.

Origin Editorial is now part of KnowledgeWorks Global Ltd., the industry leader in editorial, production, online hosting, and transformative services for every stage of the content lifecycle. We are your source for society services, market analysis, intelligent automation, digital delivery, and more. Email us at info@kwglobal.com.