First posted on the ORIGINal Thoughts Blog

Senior Solutions Manager, Wiley, Oxford, UK

Email: miwillis@wiley.com

ORCID: 0000-0002-3110-3796

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mwillispub

X: @mwillispub

Take Home Points:

Dr. A is a new post-doc doing research in ecology at a small university in a country classified by the World Bank as “low-income.” Despite having struggled to get funding, accommodations, and other essentials to see her through her undergraduate degree, her passion for her research motivated her to pursue a Master’s degree and then a PhD. Access to infrastructure and the resources necessary to carry out her fieldwork is severely limited. She’s published one article so far based on her PhD thesis. The publishing process often felt overwhelming, and she feels she succeeded largely thanks to the guidance provided by her supervisor. Now she’s looking forward to publishing her next article in your journal. How could you support her through this?

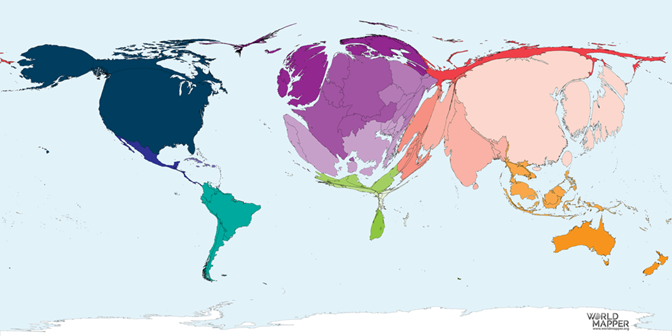

Dr. A is fictitious, but her experiences are very real. It’s easy to forget that behind every article submitted to a journal there’s an individual author’s story. That applies to authors across the world, but for junior researchers in a similar geographical context to Dr. A’s, there are many more challenges of which journal editors and editorial staff may not be aware of or sensitive to – challenges that are often a by-product of weak economies and poor infrastructure. When considering how to support such authors in getting their research published, being aware of those challenges is the best starting point. It’s vital that we address this if we are to solve the glaring inequity in global scientific research output, as vividly illustrated in Figure 1.

What follows are some themes which I hope will help get you thinking. As you’ll see, some are also pertinent to researchers outside the Global South. By way of clarification, I use the term “Global South” as a helpful shorthand expression, although it’s not strictly accurate when referring to low- and middle-income countries. There is a good discussion of this and alternative terms in this blog.

Figure 1: Territory size is proportional to the number of STEM journal articles published in 2016. The colours denote geographical region. Reproduced from Worldmapper.org under CC-BY-SA licence

Language

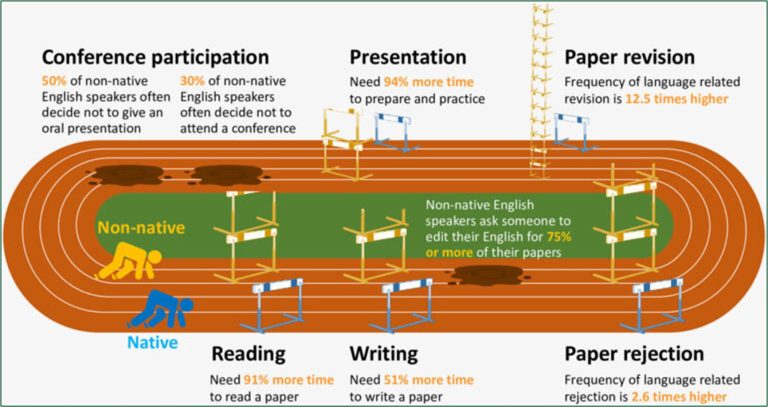

While English is the dominant language of scholarly communication, for Global South researchers English may not be their second or even third language – even in regions historically colonized by native English speakers. Figure 2, taken from a study by Amano et al. looking at “the manifold costs of being a non-native English speaker in science,” illustrates the “costs’” automatically incurred by non-native English-speaking researchers, and a survey by Arenas-Castro et al. of policies of 736 biological science journals found that “most journals make minimal efforts to overcome such language barriers in academic publishing.”

Figure 2: Estimated disadvantages for non-native English speakers when conducting different scientific activities. Amano T, Ramírez-Castañeda V, Berdejo-Espinola V, Borokini I, Chowdhury S, et al. (2023) The manifold costs of being a non-native English speaker in science. PLOS Biology 21(7): e3002184. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002184 (reproduced under CC-BY license)

As a journal editor or managing editor, your goal should be to communicate with your authors in simple and clear English at all stages of the publishing process, offer language-editing support (noting that many Global South authors won’t be able to afford charged-for services), and perhaps provide translations of author guidelines. Admittedly, it can be incredibly difficult and time-consuming for editors and reviewers to fairly evaluate a manuscript written in poor English and to discern whether it might eventually be publishable. This should compel us to provide authors with manuscript preparation and writing support, rather than to simply reject such manuscripts, potentially missing solid scientific research that was overlooked due to poor English-language writing skills. Software to improve language quality is more accessible than ever, although it’s also essential to provide careful and firm guidance about the appropriate and ethical usage of such tools (see the STM White Paper “Generative AI in Scholarly Communications”), and to be aware of potential built-in bias within some language tools against speakers of minority languages.

Bias

Nowhere is bias more likely to surface than in the editorial and peer review process, and it’s incumbent on journals to minimize the risk of conscious or unconscious bias at this stage. COPE’s Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers state, “It is important to remain unbiased by considerations related to the nationality, religious or political beliefs, gender or other characteristics of the authors, origins of a manuscript or by commercial considerations.” The UK Research and Innovation Medical Research Council has a very helpful guide to identifying where bias can creep into peer review (the original context is grant peer review, but the same principles apply to journal peer review). It shows that a single-anonymous peer review process gives greater advantage to Global North researchers and that a double-anonymous process is, therefore, more equitable. It’s also important to have a geographically diverse reviewer pool comprised of individuals who can understand the regional contexts within which research is conducted. Appointing editorial board members from under-represented areas to be ambassadors for the journal in those regions can be an effective strategy to increase the geographical spread of reviewers, since they have access to the local academic networks. Encourage ways in which more experienced – and usually more time-constrained – researchers can collaborate in peer review with younger researchers, and make sure that those younger reviewers also get the credit they deserve. For example, enable them to add the record of their peer review to their ORCID profile, and include their name in public lists of journal peer reviewers. Training and mentorship programs for reviewers can also be a very productive way of building up engagement (there’s an extremely helpful list in this ORIGINal Thoughts post): many professional societies and their journals have existing programs for their members which could be easily adapted to focus specifically on Global South researchers. This is an investment in tomorrow’s generation of reviewers and potential journal editors.

Resources

R&D expenditure in the Global South is, unsurprisingly, significantly lower than that in the Global North. Researchers may not have access to, nor be able to afford, the most up-to-date equipment or materials, and there may be immense competition for resources. It’s very costly to attend a conference, especially in another country, where the latest research is being presented – and yet it’s early career researchers from the Global South who stand to benefit most from attending. Provision of sponsorships to attend, and the post-pandemic trend towards hybrid or virtual conferences (subject to attendees having adequate internet connectivity), can help to mitigate this. Likewise, much research is still inaccessible to researchers within the Global South, although publishing partnerships with Research4Life help to address this as, of course does the huge shift towards publishing research Open Access. Offering waivers and discounts to enable authors to publish Open Access provides far greater visibility to their research, although such programs are not without challenges, discussed in this article by Rouhi et al.

Beyond this, early career researchers are often unfamiliar with publishing jargon that we take for granted. AuthorAID provides a wealth of resources to help bridge this knowledge gap, and journals can provide simple guides to help researchers by explaining what an ORCID ID is, reviewing the nuts and bolts of publication ethics, authorship and CRediT; educating them on how to comply with funder requirements, licensing, and permissions; explaining reporting checklists such as CONSORT and PRISMA; FAIR data standards, and preprints. Teaching the basics of writing a research article is important.

Geography

Another important thing journals and their editorial teams can do is to keep up to date with international news to get insights into the daily challenges faced by Global South researchers. Tropical storms, epidemics, wars, strikes, and electricity blackouts all affect email response times, the ability to meet deadlines, online access, and the availability of resources such as libraries and laboratories.

Research Equity

The World Conference on Research Integrity, held in Africa for the first time in 2022, led to the Cape Town Statement on Fostering Research Integrity through Fairness and Equity. This document provides 20 recommendations for how stakeholders, including journals and publishers, can achieve this. The statement challenges the unethical practice of so-called ‘parachute’ research (also known as “helicopter,” “parasitic,” or “neo-colonial” research), whereby well-resourced researchers from the Global North undertake research in a Global South community (a village or even a university), collect the data from that community, publish the research, and take the credit. This overlooks the contribution of that community to the research, and often means that the community gains nothing from that research. As an example, a study of articles published between 1990 and 2019 in the top 20 development journals found that fewer than one in six were authored by researchers from the Global South, even though the research was related to development in Global South regions.

Hence the Cape Town Statement calls on researchers to “contribute to local capacity development and [the] strengthening of research management systems and processes;” to ensure that research collaborations “result in appropriate benefit-sharing and recognition;” and it encourages journals and publishers to “question the practice of excluding local researchers from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) from authorship when data are from LMICs, and have a low threshold for rejecting such papers.”

When you receive a manuscript reporting research from the Global South, check that appropriate credit is given to all who contributed to the work. Consider requiring authors to provide an inclusivity statement that explains how their work involved and contributed to the community where the research was conducted. Draw on existing helpful resources such as this list of “simple rules” for researchers and initiatives that some professional bodies are now promoting (examples here, here and here).

Conclusion

The challenges faced by Global South authors will not be solved overnight, but journals have an important part to play. Each step we take can help researchers like Dr. A, whom we met at the beginning of this piece, advance towards greater academic success (Figure 3) and promote vital research that might not otherwise be published nor get the attention it deserves.

Figure 3: ‘The beginning and the end’, a bronze sculpture by David Hlongwane at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa. It depicts a proud working-class mother celebrating the academic success of her son. © Michael Willis